How to Choose the Best Chart Type to Visualize Your Data in 2024

Stop building exhibitions of charts. Start with the single most important question and choose the best chart type for your data and your users.

Charts, visualizations, or insights are the building blocks of all dashboards, so choosing the right chart type is one of the crucial skills when building a dashboard. Pick the wrong one, and you can confuse or misinterpret the data or even make a wrong business decision with a lasting impact.

In this article, I will share my experience designing real-life business dashboards and other data-heavy applications, focusing on chart types.

In the previous post about building dashboards users actually love to use, I discussed the general principles of building a dashboard. In this one, I’ll focus on the details of the dashboard’s building blocks: the charts. And you better know your charts well before building the dashboard. So let’s get started.

Start with the use case - ask the most important question first

I could just list all available chart types here like in every other article on the internet, but I think this approach leads to thinking chart-first and creating already mentioned exhibitions of charts. And you don’t want to build an exhibition. You want to deliver a message with your charts and dashboards - to have an impact on your users. Keep that in mind whenever you feel the urge to use the random but nice-looking chart you just saw in some infographics!

When deciding which chart to use, you should always start with the most important question:

What do I want to show to my users?

Show one big number

Compare values within and between groups

Show the composition of data

Display change over time

Explain the relationship or flow between metrics

Plot geographical data

Show the details of many items

These seven use cases will cover 99% of your data visualization needs. If you answer the question with a use-case, meaning with what you want to deliver as a message, and not directly with the chart type, you’re on the right path. Let’s now dive deeper into the details.

Show one big number with a Headline

Just because you have numbers, there is not necessarily a reason to create a chart. Showing a Headline (or KPI - key performance indicator) is a great way to convey critical metrics, whether you build a marketing, project management, or supply chain dashboard. Good examples of Headline-worthy numbers are the following metrics:

Number of sold items

Gross revenue, net revenue

Number of visitors to a website

Two very important pieces of information must come along with a Headline:

The related date range or time frame means the time span represented by the Headline. Typically, this is a date filter on the dashboard or indicated in the title. There is a big difference between yesterday’s and last year’s gross revenue, and the user should be told which he is looking at.

Context. Showing the number alone is not enough. You need to give it context, such as showing the difference from the previous period, showing a secondary metric, or comparing it with another metric. Users cannot tell if the number should make them smile or cry without context.

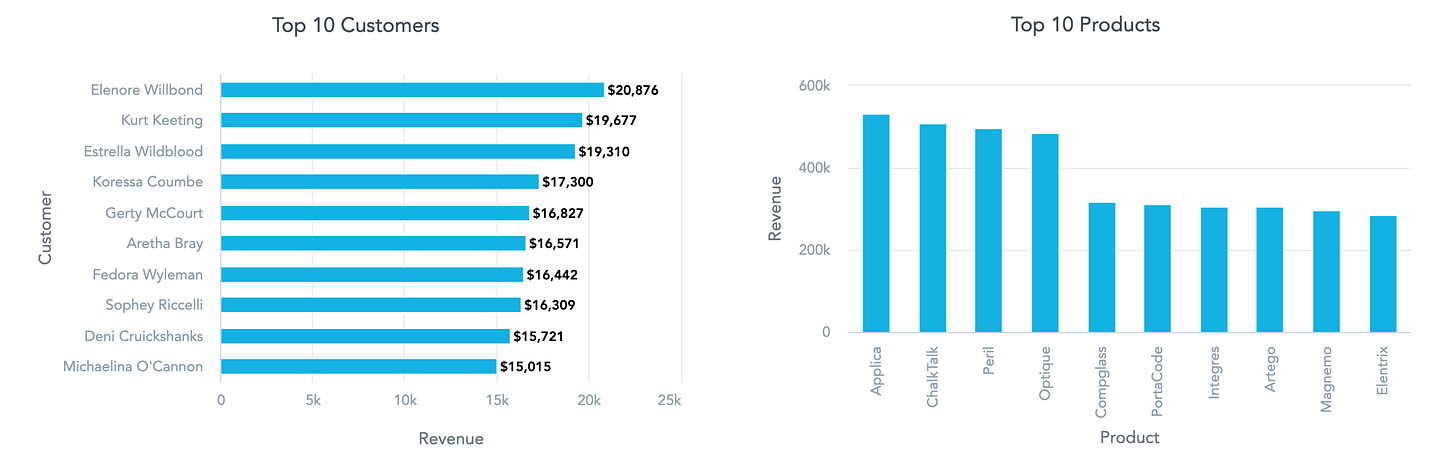

Compare values within and between groups using a bar chart, column chart, or bullet chart

One of the dashboard's most common use cases is comparing countries, products, departments, etc.

What is the population in European countries?

What are my sales numbers in those countries?

Who are the top salespersons in my company?

All these questions can be answered by the most well-known and used charts - bar charts and column charts. These names are sometimes used interchangeably, but typically, the columns are vertical, and the bars are horizontal (to remember the direction - picture all those ancient Roman buildings with columns). The meaning stays the same - the length of the bar (or column) represents the value. Don’t shy away from using bar and column charts. They might be omnipresent and well-known by users, but that is their biggest strength - they convey the message in the most understandable way.

Both bars and columns in your charts can be grouped (sometimes called clustered). For example, if you want to show the comparison not just between countries but also within countries, the grouped bar chart is a good option to show, e.g., the average age in countries (group) but also between men and women.

Another option is to stack (or segment) bars in your chart. This step further divides the data in each bar (column), meaning the chart can answer questions like sales in different regions and across multiple product categories. The bars in the stacked bar chart can be a simple sum of values to show the total, or all bars can be stacked to 100% to show the relative value of each category.

You might need to go one step further beyond simple comparison. For example:

Who are the top salespersons in my company, and what are their goals?

How is this person doing in comparison to a company benchmark?

A bullet chart is a great way to display answers to such questions. The main bar displays the current value, the secondary bar can show, for example, a previous period value, and the symbol marker typically indicates a goal or benchmark value.

Show the composition of data utilizing a pie chart, donut chart, treemap, pyramid, or funnel charts

Anytime you need to show a simple composition or part-to-whole (how the share relates to the total amount), this class of charts comes in handy. For example:

Allocation of women and men among your customers

Approved and denied applications for a school

Share of 1 region’s sales on the whole company sales

These kinds of questions could be very well answered by a pie chart or donut chart. On the other hand pie and donut charts should come covered in black and yellow warning signs saying do not use for more than two or three categories! Humans are awful at comparing angular distances – the sizes of slices – if there are too many. If you want to compare more categories, skip these two and read on.

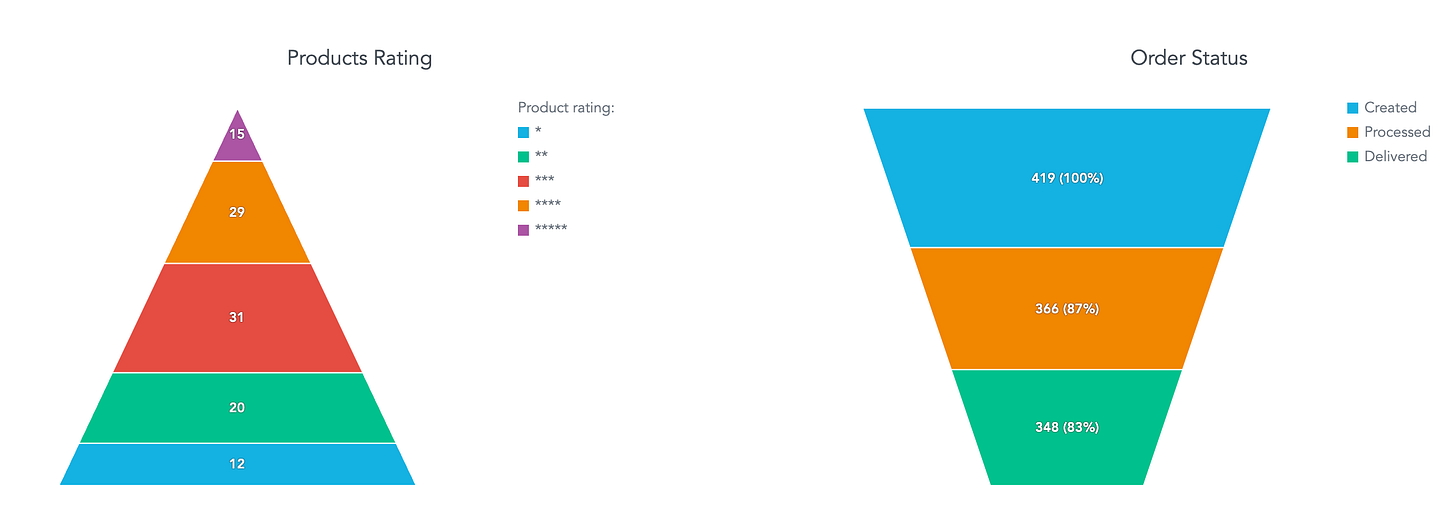

A pyramid chart can be highly effective when you want to display data in a hierarchical structure with a clear progression from one level to the next. It helps to answer the questions like these:

How does the number of top-level executives compare to entry-level employees?

What is the breakdown of product sales through different tiers?

What are the proportions of employees at different job levels within the organization?

Funnel charts are inverted pyramids, and they are perfect for showing a linear process that has multiple stages, particularly when there is a noticeable drop-off from one stage to the next. For example:

What percentage of leads move through each stage of the sales funnel?

At which stage do we lose the most potential customers?

How effective is our onboarding process in retaining new users?

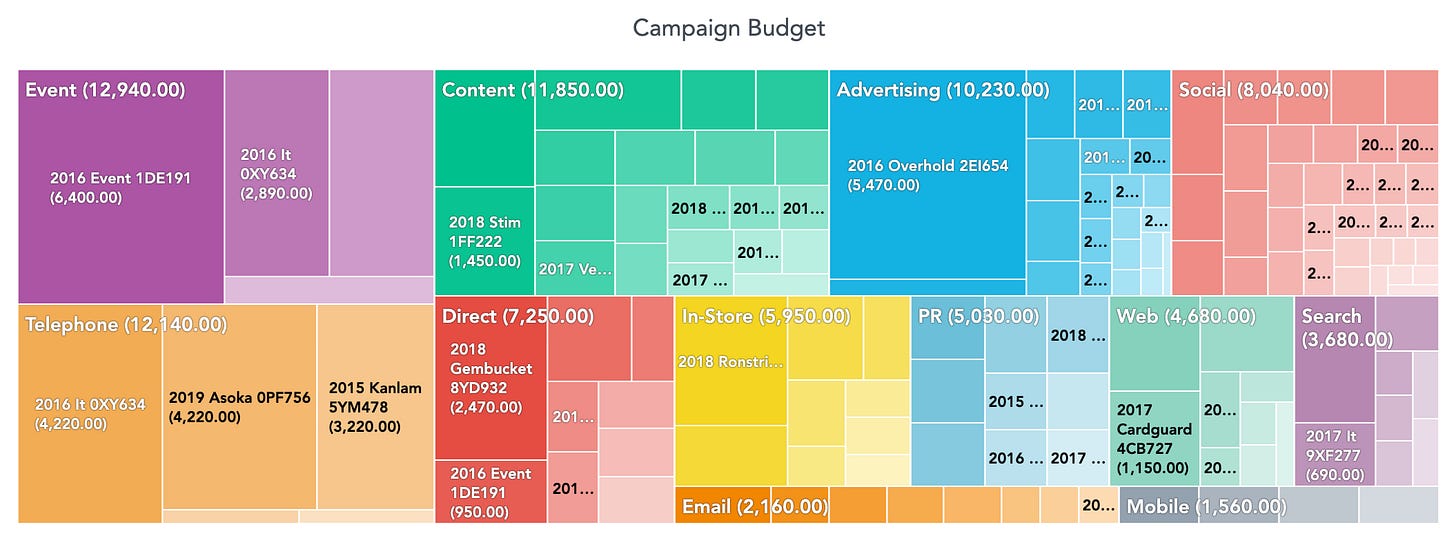

Imagine you need to display an even more complex composition, such as a two-level hierarchy. This is where a treemap becomes particularly useful. For example:

Population distribution: Showing the number of humans per continent and then breaking it into individual countries.

Marketing budget allocation: Displaying the budget across different marketing campaign categories and further detailing specific campaigns within each category.

Sales performance: Highlighting overall sales by product categories and then delving into individual sales within each category.

A treemap is ideal for visualizing such compositions. Its rectangular layout allows for a more intuitive understanding of hierarchical data. Each rectangle represents a category, with the size of the rectangle corresponding to its value. Within each category, smaller rectangles represent subcategories, making it easier for the human brain to compare areas and perceive the relative sizes of each segment.

Display change over time with a line chart, area chart, or column chart

Showing the evolution of any metric over time is one of the most common use cases while designing a dashboard. A few examples might be:

Sales trend over the past year

Number of webpage visitors trend

Amount of support tickets coming to your help desk day by day

All those use cases have in common that they show the progress of a metric in time. The change from one period to another is the key message these charts communicate.

A line chart, area chart, and column chart are the most common chart types used to visualize change over time. In most cases, they can be used interchangeably, but subtle differences exist between them. Line and area charts are the best tools to visualize data that goes up and down daily. For example, the number of tickets in your backlog, the amount of money in a bank account, or the temperature. On the other hand, column charts are the best choice for data that starts at zero every period. Like the daily number of support tickets, monthly sales numbers, or webpage visitors.

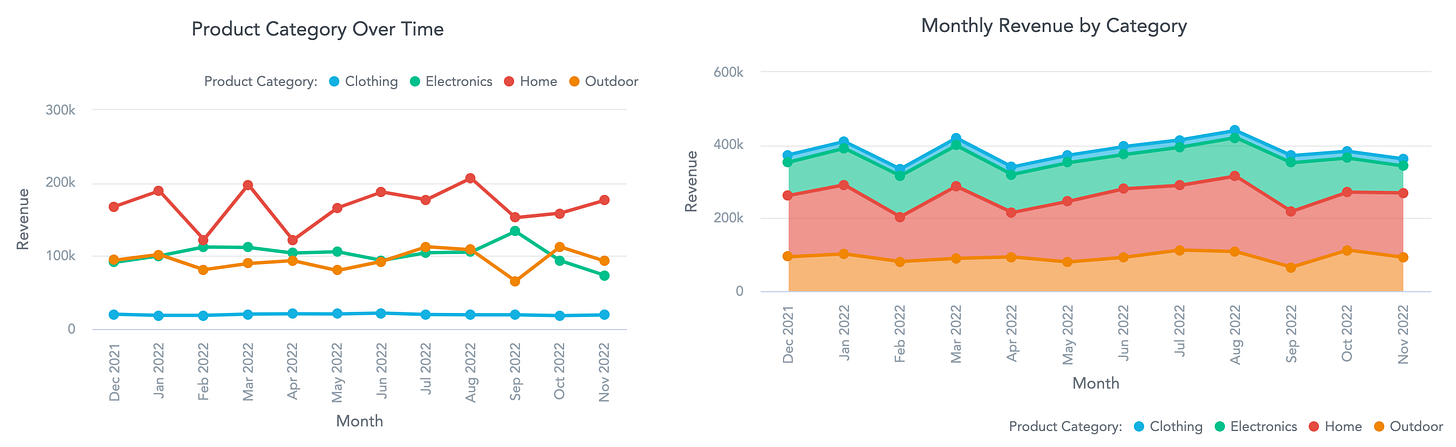

Now imagine you want to display a sales trend of your four different product categories. What is the key message here? Do you want to compare them against each other or show their share of the overall sales performance? The former is best done with a line chart with multiple lines, the latter with a stacked area chart.

One last example of displaying time, although on a cyclical basis, the most popular are hours, days, or months. For example, what are the busiest hours on your hotline during the week? Heatmap is a fantastic type of visualization for exactly this use case.

Explain the relationship or flow between metrics with a scatter plot, bubble, combo, or waterfall chart, dependency wheel, or Sankey diagram

Explaining a relationship or correlation between two metrics can be very beneficial since it’s one step towards getting valuable insights from the data. If you ever need to answer a question like the following examples, the scatter plot is the best choice:

How does the campaign spend relate to its revenue across many different campaigns?

What is the relationship between the number of orders and total revenue by the product category?

How many courses did each student start and finish?

Each campaign, product category, or student is represented by the dot on the chart, and each metric is then encoded on one of the X and Y axes.

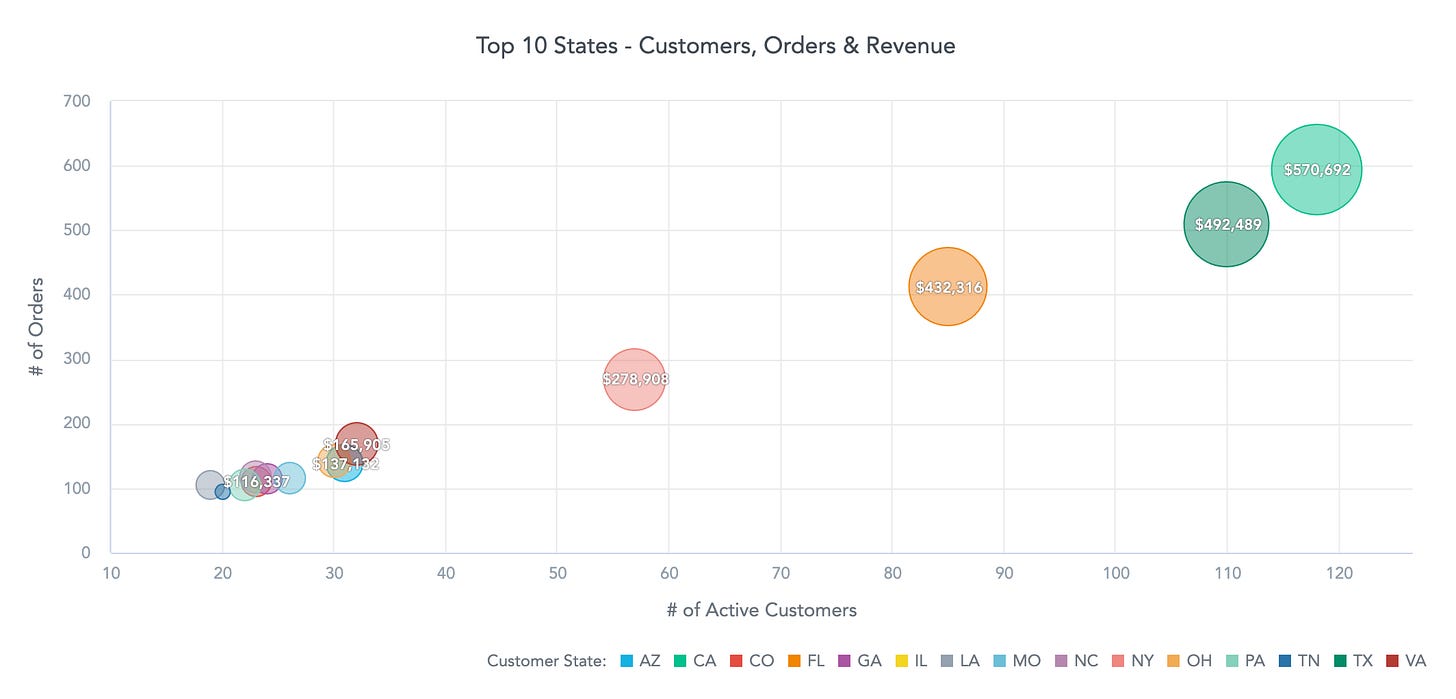

Adding a third metric to the mix brings an extra level of insight but also an extra level of complexity. This additional metric is typically represented by the size or the color of the dot, which then becomes a bubble and, therefore, a bubble chart. A few example questions that can be answered with bubble charts are:

How many courses did each student start and finish (X and Y axis), and what university did they study at (bubble color)?

What is the relationship of the company’s total revenue in each country (bubble size) to the number of stores in that country (Y-axis) and to the number of employees in that country (X-axis)?

Or one of the most famous bubble charts by Hans Rosling - how do the country’s GDP per capita (X-axis) and population (bubble size) relate to life expectancy (Y-axis)?

Relationships or correlations between two metrics can also be shown over time. For example, the number of visitors and the revenue of the e-commerce website. In that case, a combo chart consisting of a column chart and a line chart comes into play. With two independent Y axes, it is possible to show the relationship even between metrics with vastly different scales.

Waterfall charts are ideal for showing how an initial value is affected by a series of intermediate positive or negative values, leading to a final value. They provide a clear visual representation of the cumulative effect of sequential data, answering questions like:

How did each department contribute to the company's quarterly profit?

What were the main drivers behind changes in net profit?

How did individual expenses and savings impact the project budget?

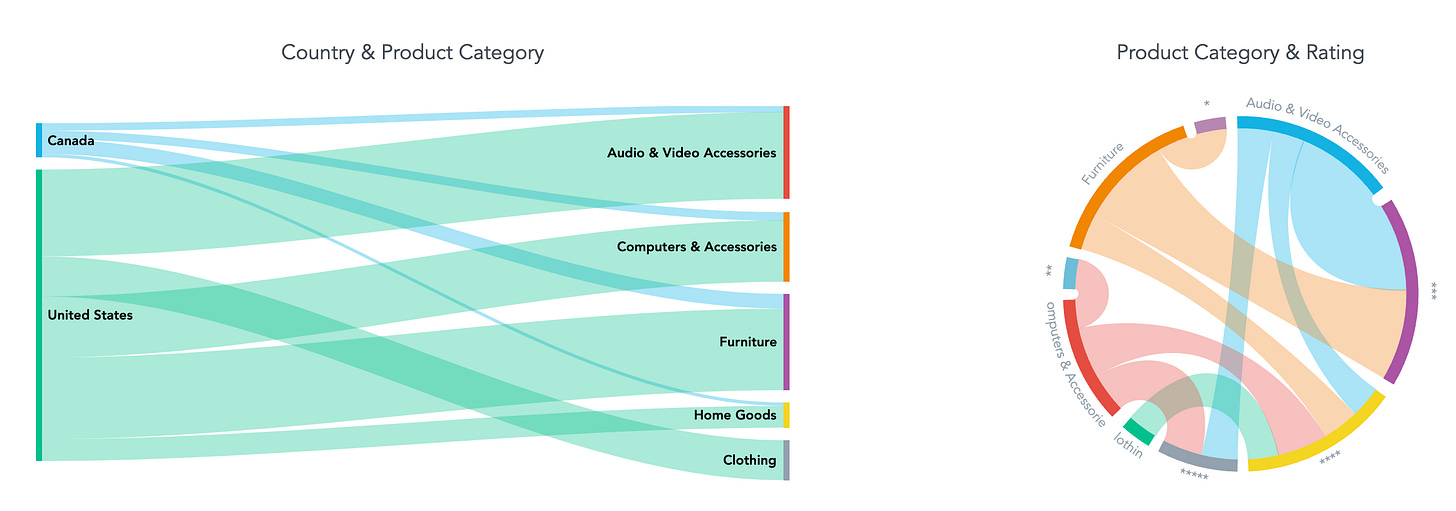

Dependency wheels are powerful tools for visualizing the relationships and dependencies among multiple entities or variables in a circular layout. They are frequently used in network mapping, supply chain analysis, and project management to illustrate complex connections. By using dependency wheels, you can answer questions such as:

How are software modules interconnected?

What are the key interactions between departments?

Which tasks in a project are interdependent?

Sankey diagrams are excellent for showing the flow of resources, such as energy, money, or data, between different stages or entities. They make it easy to follow the movement and proportion of resources. Typical use cases include:

Tracking the flow of funds in a budget.

Visualizing the energy consumption and losses in a system.

Mapping the distribution of traffic on a website from different sources.

Plot geographical data on the map

Whenever you need to display geographical data, it’s kind of obvious to put them on a map. For example:

Distribution of customers across states

Number of people living in the cities

Revenue per region

The location is a generally understood concept, and a map provides a direct connection to the data. On the other hand, having geographical data does not mean the map is the best option. For example, if you need to display a relationship between two different metrics for a single geographic location, e.g., the number of stores in a state and the average sales for that state, it’s better to go back to scatter of bubble charts than try to cram too much information on the map.

There are two main ways to display data on a map. To fill the area (e.g., a state) or to use a pushpin or other shape over the target area. In most cases, I would suggest using the pushpin on the map over the filled areas (a filled map is sometimes called a choropleth). Why? Because the size is psychologically perceived as a stronger indicator than the color shade. Therefore the poorly performing large states (let’s say Alaska) will overshadow much better-performing small states (for example, Massachusetts). In other words, geographic significance does not translate to data value significance.

Also, be sure to use the map only as a background; the data points are the stars of the show.

Show the details of many items as a good old table or repeater

Yes, although they might not be the most striking kind of visualization, tables sometimes have their place on the dashboards. The fact that you have data to show does not mean they need to be shown as a chart. Sometimes, the best shape for the data is still the humble table.

The table needs to make sense in the context of the whole dashboard, though. For example, a dashboard focused on orders from the e-commerce store, showing various overviews and summary charts, and in the end, it can show all the separate orders in a table. So you can see the order details or even drill from the dashboard directly into your system to see all the details of that particular order. Other examples could be:

Product details - product category, items sold, average price, % of revenue

Customer details - name, email, # of orders, total revenue

Support agents - name, position, # of assigned tickets, # of resolved tickets, CSAT

Generally, if you need to list details of a group of items, the table is usually a good choice. Especially if it’s part of the dashboard, it is interactive and allows users to sort columns, drill into other dashboards, etc.

Last but not least, having at least one table on the dashboards could also serve as a negotiation trick for the more stubborn stakeholders unwilling to leave Excel, their safe and familiar space.

Repeater is a sort of fancy table containing small charts. It is a versatile tool for showing detailed data in a structured, repeating format. It is particularly useful when you need to present a lot of items with multiple data points, such as:

Product performance across different metrics

Employee performance metrics

Monthly sales figures for multiple products

Repeater combines the information density of tables with the visual clarity of charts. Each cell in a repeater can display data as numbers, bar charts, or line charts, with additional support for rich text content, including images and links. This flexibility allows for a comprehensive and interactive data presentation.

Stay boring, avoid exotic chart types

So, the other day, you went on the internet and found some exciting visualization to spice things up a little on your dashboard – something like you can find in the Xenographics zoo of data visualizations. Well, forget about it. Some of those charts might look cool on some fancy infographics but not on your typical dashboard. Again, the dashboard is about understandability. Be a little boring with the chart types on purpose. The users of your dashboards will thank you.

Summary of the key principles

We’ve explored 99% of the most common use cases of data visualization and the most useful chart types. The visual part of the data presentation is really important, but remember that the focus should be on following the use case and delivering the message to your audience. Adhere to the mentioned principles, and you can't go too wrong.

Start with the use case

Show one big number with a headline

Compare values within and between groups using a bar chart, column chart, or bullet chart

Show the composition of data utilizing pie charts, donut charts, treemaps, pyramids, or funnel charts

Display change over time with a line chart, area chart, or column chart

Explain the relationship or flow between metrics with a scatter plot, bubble, combo, or waterfall chart, dependency wheel, or Sankey diagram

Plot geographical data on the map

Show the details of many items as a good old table or repeater

Stay boring, avoid exotic chart types

Do not build exhibitions of charts. Build usable and understandable dashboards instead!

If you want to try any of the mentioned charts, you can register for the GoodData trial and play with them on your own.

This article was originally published in December 2022. In July 2024, it was updated and expanded with more chart types supported by the GoodData platform.